On a personal note: Writing about gems can be tricky business. As a journalist, you might write that you’re bringing clarity to a story — but if you’re also a gemologist, that word hits differently. You don’t just read “clarity,” you see one of the 4Cs. You start thinking about grades, inclusions, maybe even reaching for the grading report.

The same goes for when writing about “phenomenal” gems. As a gemologist, the term phenomenal is reserved for only those gems with special powers:

asterism, showing a star;

chatoyancy, showing a cat’s-eye;

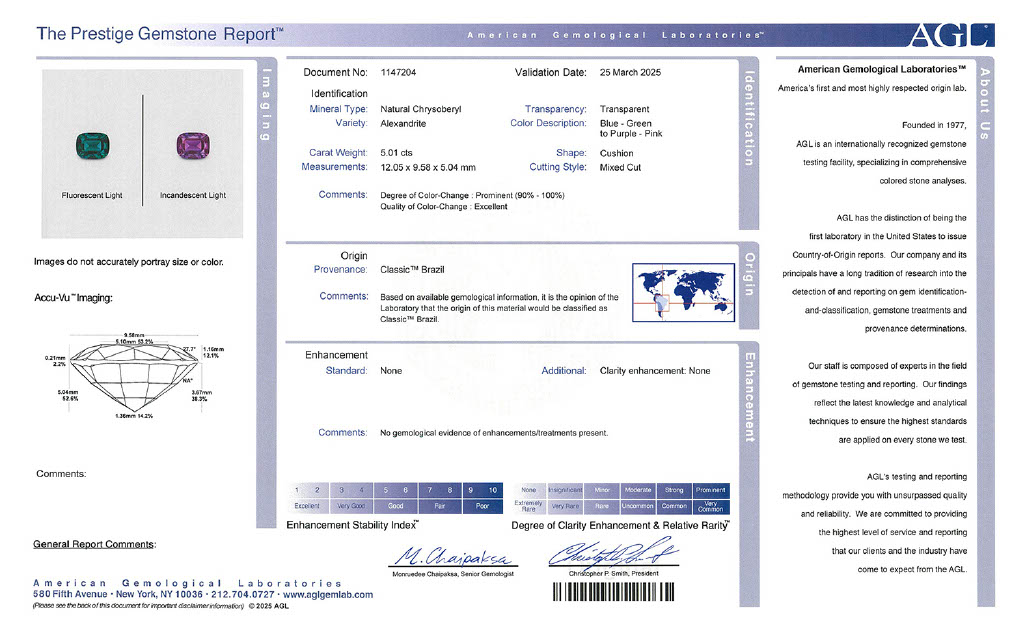

color-change, the changing of color in different lighting situations, as with an alexandrite;

adularescence, presenting a billowy blue or white light, sometimes in rainbow colors, as in a moonstone;

play-of-color, presenting a multitude of colors from the diffraction of visible light by closely packed silica spheres, as in an opal;

labradorescence, showing flashes of color, caused by interference of light within microscopic layers of feldspar, as with labradorite;

iridescence (or Orient), a rainbow of colors seen on the surface (or near the surface), caused by interference and diffraction of light reflecting from thin layers of nacre, as with pearls.

While the journalist can wax poetic about phenomenal gems when reporting on important or most beautiful jewels, the gemologist must reserve “phenomenal” for only those that have certain gemological characteristics.

And this is where our pictorial begins — two phenomena, Color-Change and Chatoyancy, with four beautiful – and “phenomenal” – gems! – gr

Phenomenal Gems

Phenomenal gemstones do more than just display beautiful color—they exhibit those unusual optical effects (above) caused by the way light interacts with their internal structures. Such effects aren’t just eye-catching—they’re diagnostic, helping gemologists identify both the species and the cutting orientation of the stone. Collectively, these optical properties are known as phenomena, and the stones that display them are called phenomenal gems.

Why Do Some Gems Change Color?

One of the most fascinating optical effects in gemology is color-change—when a gemstone appears dramatically different in hue under daylight (or daylight equivalent – usually fluorescent lighting) compared to candle light (or candle light equivalent – usually incandescent light). Classic examples include alexandrite, color-change sapphire, color-change garnets, and certain rare color-change spinels. But not all gems that look different under different lighting actually change color. Many only shift in color, and that difference is key.

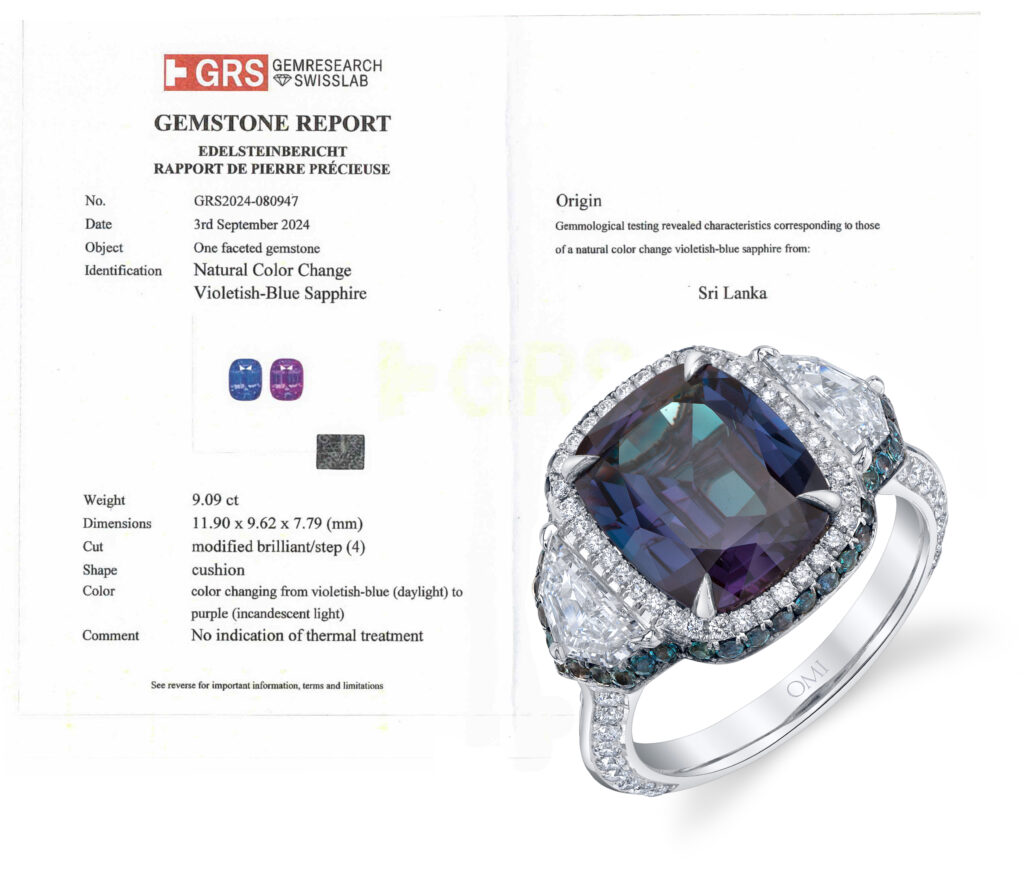

surrounded by diamonds and alexandrites. From Omi Privé, Los Angeles.

Color Change vs. Color Shift: What’s the Difference?

In gemology, the term color-change is reserved for stones where the perceived hue under one light source moves across the color wheel to a distinctly different hue under another light source—for example, bluish-green to purplish-red, or greenish-blue to reddish-purple. The change is usually striking.

By contrast, color shift describes a more subtle transformation—often within a narrow range on the color wheel. A gem might go from blue to greenish-blue, or pink to slightly orangy-pink. You’ll see a difference under varying lights, but it doesn’t feel like the gem has ‘changed color’—just that the hue has shifted slightly, not enough to register as a truly different color.

Why does this happen?

It’s All About Light and Chemistry

Color-change and color-shift effects both depend on two things:

1. The Gem’s Chemistry

Certain trace elements—chromium, vanadium, and iron—cause gems to absorb specific wavelengths of light. The gem’s crystal structure then influences which parts of the spectrum are absorbed (held) or transmitted (returned to your eyes). This is why chromium causes a deep red in ruby, but a green-red change in alexandrite.

2. The Type of Light Striking the Gem

Light sources vary:

Daylight and fluorescent light contain more blue and green wavelengths.

Incandescent and candlelight are rich in red and orange wavelengths.

A gem that absorbs in the middle (yellow) of the spectrum and allows both ends of the spectrum (blues, greens, and reds) to be returned to the eye, will appear greenish in daylight and reddish in incandescent light—the classic alexandrite effect.

If the gem’s absorption is more narrow or less dramatic, then we see a color shift – not a color-change.

From Omi Privé, Los Angeles.

Always Looking at Color – Niveet Nagpal, Omi Privé

“When you look at purple sapphires and purple spinels, many of them do have color shift,” says Niveet Nagpal, owner of Omi Privé, an award winning wholesale gem and jewelry firm in Los Angeles. He’s always looking at color. “I have a color shifting lamp on my desk.”

Nagpal hits the button and the lamp switches light sources so when he’s looking at stones, he can see how they look in different lighting. Is there a shift? Is there a change?

“I notice that a lot of purples will have some shift to them. And sometimes the shift is strong enough that they’ll put it on the report as a color-change.”

Other times, the color shift will just go in the comments as the stone experiences some color shift, but not enough for a color-change call on the report.

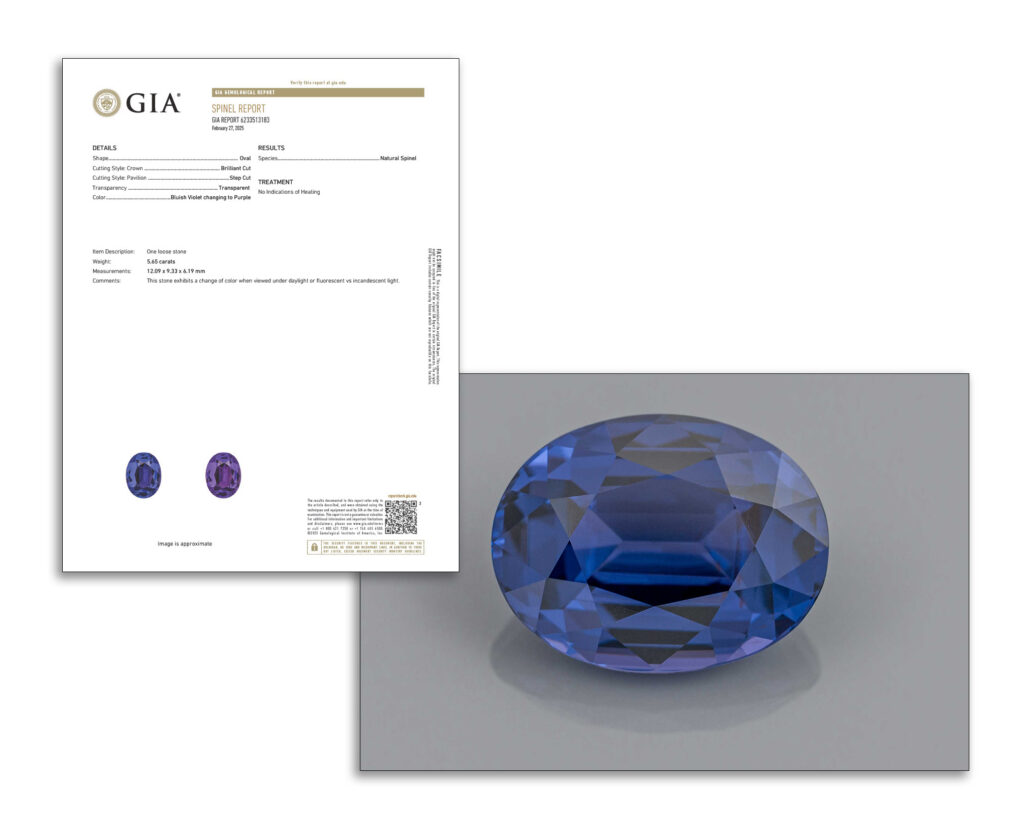

Speaking about the Color-Change Spinel oval seen above, Nagpal notes, “this one was interesting! We’ve been doing a lot of business with cobalt spinels from Tanzania. And those are very distinct. They’re generally more blue than this one, from steely blue to a neon blue. This type of spinel has a good amount of cobalt! And they really face up blue. So there’s no doubt that those are cobalt!”

“This 5.85-carat spinel was originally shown to me as a ‘cobalt spinel’,” says Nagpal. This stone has more purple. Now, it does change to blue in cooler light… but just not quite like the Tanzanian cobalt blues.

“When I sent it to both AGL and GIA, they said that there is cobalt, but not a significant amount of cobalt [to be called “Cobalt Spinel”]. Color in these are from Vanadium. That’s giving it the purple.”

So the labs did not identify the 5.85-carat spinel as a “Cobalt Spinel.” “I just love the stone, regardless of what anybody wants to call it!” says Nagpal.

“I was able to acquire the stone, and then when I sent it in [to the labs], it did get a ‘color change.'”

“I guess that’s why it’s giving us a nice change… because it does have just enough cobalt and vanadium.”

From Omi Privé, Los Angeles.

From Omi Privé, Los Angeles.

The Science Behind Cat’s-Eye Chrysoberyl

The term cat’s-eye, when used without qualification, refers specifically to cat’s-eye chrysoberyl—a gem valued for its ability to produce a very straight, sharp cat’s-eye.

What Creates the Cat’s-Eye Effect?

The optical phenomenon known as chatoyancy occurs best when a direct light source reflects off parallel inclusions—typically rutile needles or hollow tubes—within the gemstone.

When the stone is cut as a dome, “en cabochon,” light entering the gem reflects off the aligned inclusions and is directed back toward the viewer. Because of the curved surface of the cabochon, these reflections are focused and concentrated into a single sharp band of light—the “eye.”

The best result is a straight, sharp, centered eye that moves cleanly across the surface as the light—or the gem—is moved.

Why Transparency Matters

As with other phenomenal gems such as star sapphires and rubies, cat’s-eye chrysoberyl is most highly valued when it is semi-transparent. Better transparency allows light to interact more cleanly with the internal structure, resulting in a sharper, more focused eye.

A strong contrast between the bright eye and the body color of the gem is also more visible in stones with good transparency.

Color Counts, Too

Top cat’s-eye chrysoberyl shows a rich golden-honey to brownish-golden hue. Greenish or overly yellow stones are considered less desirable.

There is also an optical feature that occurs when you direct the spotlight to the side of the eye. This produces a darker side (on the side of the light source), and a lighter side (the side away from the light source), and is what gemologists refer to as the “milk and honey” effect.

One Eye—or Two?

Under a single point light source, the gem shows a single crisp eye. But when viewed under two separated light sources, a second eye appears, one eye for each light source. As the stone moves, the twin reflections can make the eye appear to open and close, adding to the lifelike, almost animate quality of the effect.

Dispersion

While not considered one of the “phenomena,” demantoid garnets have the capability to produce flashes of rainbow colors, called dispersion, or colloquially ‘fire,’ that you see in diamond (which is one of the reasons demantoid – meaning diamond-like – got its name.) So all the more special to have demantoid garnets with their “phenomenal” dispersion, surrounding the phenomenal cat’s-eye.

Although not classified as a “phenomenon,” dispersion—flashes of rainbow color often referred to as fire—is another valued optical feature in some gems. Demantoid garnets, for example, are well known for their strong dispersion. In the ring seen here, we have a chrysoberyl cat’s-eye, alexandrites, and demantoid garnets, all giving us a fabulous phenomenal light show!

Special thanks to Niveet Nagpal of Omi Privé, Los Angeles.